MOTOROLA CMOS LOGIC DATA

CHAPTER 7

7–2

RELIABILITY

Paramount in the mind of every semiconductor user is the

question of device performance versus time. After the

applicability of a particular device has been established, its

effectiveness depends on the length of troublefree service it

can offer. The reliability of a device is exactly that — an

expression of how well it will serve the customer. The

following discussion will attempt to present an overview of

Motorola’s reliability efforts.

BASIC CONCEPTS

It is essential to begin with an explanation of the various

parameters of Reliability. These are probably summarized

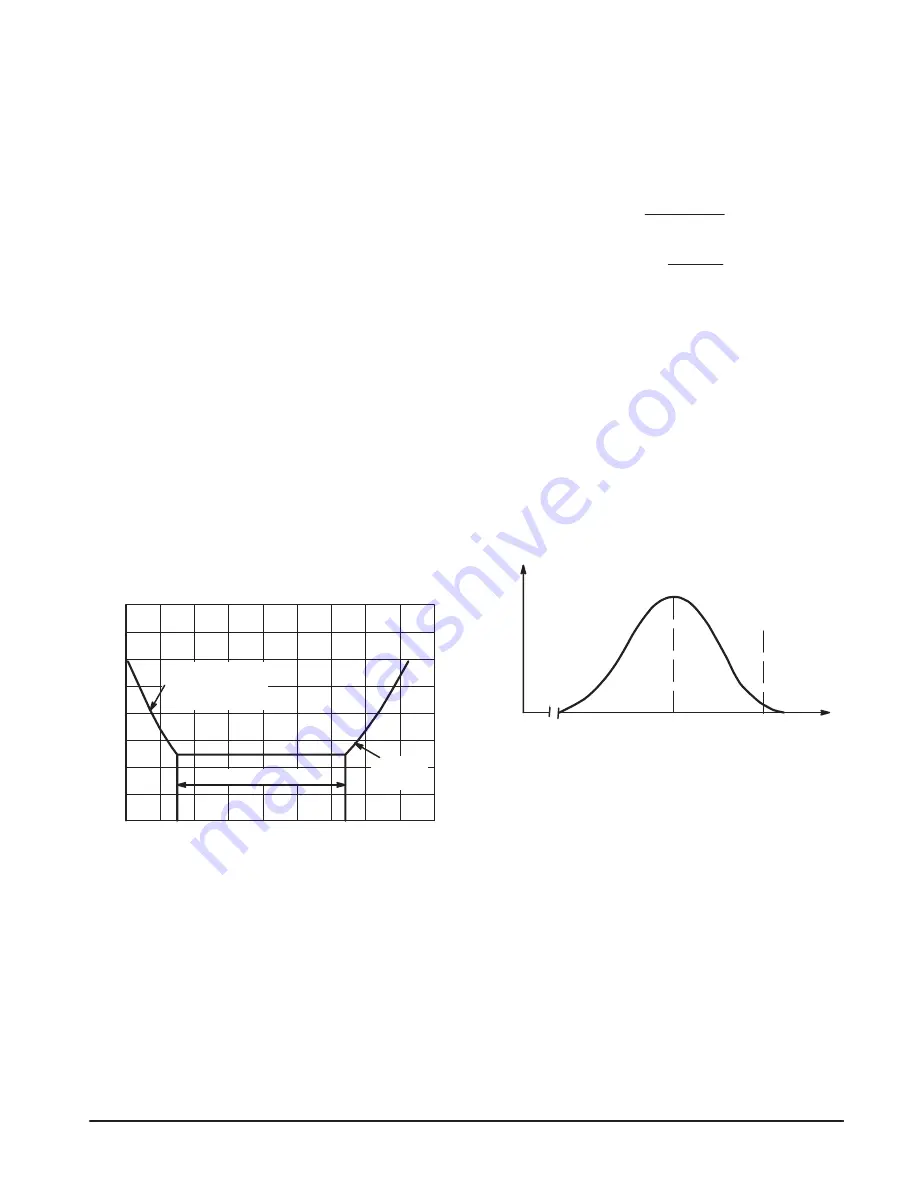

best in the Bathtub Curve (Figure 1). The reliability perfor-

mance of a device is characterized by three phases: infant

mortality, useful life, and wearout. When a device is

produced, there is often a small distribution of failure

mechanisms which will exhibit themselves under relatively

moderate stress levels and therefore appear early. This

period of early failures, termed infant mortality is reduced

significantly through proper manufacturing controls and

screening techniques. The most effective period is that in

which only occasional random failure mechanisms appear.

The useful life typically spans a long period of time with a

very low failure rate. The final period is that in which the

devices literally wear out due to continuous phenomena

which existed at the time of manufacture. Using strictly

controlled design techniques and selectivity in applications,

this period is shifted well beyond the lifetime required by the

user.

Figure 1.

TIME (HOURS)

FAILURE RA

TE

INFANT MORTALITY

(SUCH AS EARLY

BURN–IN FAILURES)

WEAROUT

FAILURES

USEFUL LIFE

1,000,000

100,000

10,000

1000

100

10

Both the infant mortality and random failure rate regions

can be described through the same types of calculations.

During this time the probability of having no failures to a

specific point in time can be expressed by the equation:

Po = e–

λ

t

where

λ

is the failure rate and t is time. Since

λ

is changing

rapidly during infant mortality, the expression does not

become useful until the random period, where

λ

is relatively

constant. In this equation

λ

is failures per unit of time. It is

usually expressed in percent failures per thousand hours.

Other forms include FIT (Failures in Time = (%/103 hrs) x

10–4 = 10–9 failures per hour) and MTTF (Mean Time To

Failure) or MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures), both being

equal to 1/

λ

and having units of hours.

Since reliability evaluations usually involve only samples

of an entire population of devices, the concepts of the Cen-

tral Limit Theorem apply and

λ

is calculated using x2 distribu-

tion through the equation:

x2 (x, 2r + 2)

2nt

λ

v

100 – CL

where x =

100

CL = Confidence Limit in percent

r = Number of rejects

n = Number of devices

t = Duration of test

The confidence limit is the degree of conservatism desired

in the calculation. The Central Limit Theorem states that the

values of any sample of units out of a large population will

produce a normal distribution. A 50% confidence limit is

termed the best estimate and is the mean of this distribution.

A 90% confidence limit is a very conservative value and

results in a higher

λ

which represents the point at which 90%

of the area of the distribution is to the left of that value

(Figure 2). The term (2r + 2) is called the degrees of freedom

and is an expression of the number of rejects in a form

suitable to x2 tables.

Figure 2.

50% CL

FREQUENCY

90% CL

λ

, FAILURE RATE

The number of rejects is a critical factor since the definition

of rejects often differs between manufacturers. While

Motorola uses data sheet limits to determine failures, some-

times rejects are counted only if they are catastrophic. Due to

the increasing chance of a test not being representative of

the entire population, as sample size and test time are de-

creased, the x2 calculation produces surprisingly high values

of

λ

for short test durations even though the true long term

failure rate may be quite low. For this reason relatively large

amounts of data must be gathered to demonstrate the real

long term failure rate.

Since this would require years of testing on thousands of

devices, methods of accelerated testing have been devel-

oped.

Years of semiconductor device testing has shown that

temperature will accelerate failures and that this behavior fits

the form of the Arrhenius equation:

R (t) = R0(t)e –

θ

/kT

Summary of Contents for CMOS Logic

Page 1: ......

Page 5: ...iv MOTOROLA CMOS LOGIC DATA ...

Page 6: ...Master Index 1 ...

Page 12: ...Product Selection Guide 2 ...

Page 17: ...The Better Program 3 ...

Page 20: ...B and UB Series Family Data 4 ...

Page 25: ...CMOS Handling and Design Guidelines 5 ...

Page 32: ...CMOS Handling and Design Guidelines 5 ...

Page 39: ...Data Sheets 6 ...

Page 234: ...MOTOROLA CMOS LOGIC DATA MC14174B 6 196 FUNCTIONAL BLOCK DIAGRAM TIMING DIAGRAM ...

Page 238: ...MOTOROLA CMOS LOGIC DATA MC14175B 6 200 FUNCTIONAL BLOCK DIAGRAM TIMING DIAGRAM ...

Page 555: ...CMOS Reliability 7 ...

Page 561: ...Equivalent Gate Count 8 ...

Page 563: ...Packaging Information Including Surface Mounts 9 ...

Page 571: ......