Operator's Manual

Issue 14

/

Mar 2016 / UMC0071

Mercury

iPS

©2016 Oxford Instruments NanoScience. All rights reserved.

Page

41

usually used to energise the magnet to a target current (switch heater ON) then to run down the

power supply, with the switch heater OFF, to leave the magnet energised at the target current.

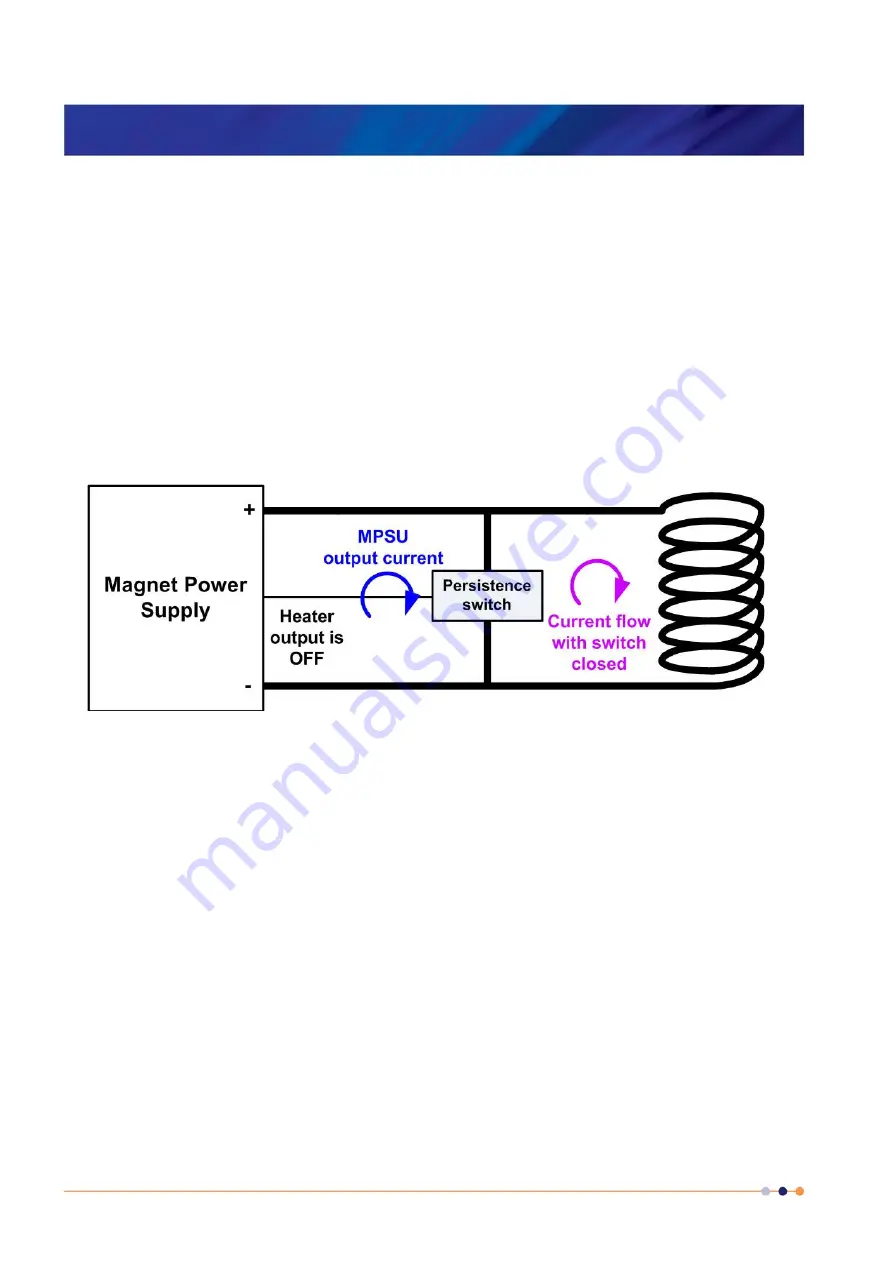

The basic configuration is shown in Figure 8 (protection circuits not shown). It is important to

remember that the current in the switch equals the difference between the magnet current and

the power supply current

=

−

thus when running down the leads (power supply) after energising a magnet the switch will be

approaching its maximum as the power supply current approaches zero. It is important not to

ramp the leads too fast as this is the rate at which current is building in the switch. Switches

can quench (break open) because they over heat if they are ramped too fast.

Figure 8. Diagram showing a simple solenoid magnet fitted with a persistence switch. In this example the persistence

switch heater is OFF, the switch is “closed” (analogy with relay contacts), so current flows through the switch so two

current loops exist. The current in the switch is the difference between the psu current and the magnet current.

At the instant when the switch opens (or closes) there will be a perturbation in the power supply

output as the relatively large inductance load of the magnet is connected (or disconnected) from

the psu and the control loop time constant changes.

4.1 Quench

In normal magnet operation this is a very unusual event. This is when the superconductor of

the magnet coil(s) reverts to its normal resistive state. For low-temperature superconductors

such as NbTi and Nb

3

Sn the propagation of the normal state is very fast and the electrical

resistance rise is large. The results of this transition is a rapidly rising voltage transient across