59

An example of proportioning would be a vehicle approaching a stop sign

at an intersection. If the driver were traveling at 50mph and only applied

his brakes once at the intersection, his car would skid through the inter-

section before coming to a full stop. This illustrates how On/Off control

acts. If, however, the driver started slowing down some distance before

the stop sign and continued slowing down at some rate, he could con-

ceivably come to a full stop at the stop sign. This illustrates how propor-

tional control acts. The distance where the speed of the car goes from

50 to 0 MPH illustrates the proportional band. As you can see, as the car

travels closer to the stop sign, the speed is reduced accordingly. In

other words, as the error or distance between the car and the stop sign

becomes smaller, the output or speed of the car is proportionally dimin-

ished. Figuring out when the vehicle should start slowing down depends

on many variables such as speed, weight, tire tread, and braking power

of the car, road conditions, and weather much like figuring out the pro-

portional band of a control process with its many variables.

The width of the proportional band depends on the dynamics of the sys-

tem. The first question to ask is, how strong must my output be to elimi-

nate the error between the setpoint variable and process variable? The

larger the proportional band (low gain), the less reactive the process. A

proportional band too large, however, can lead to process wandering or

sluggishness. The smaller the proportional band (high gain), the more

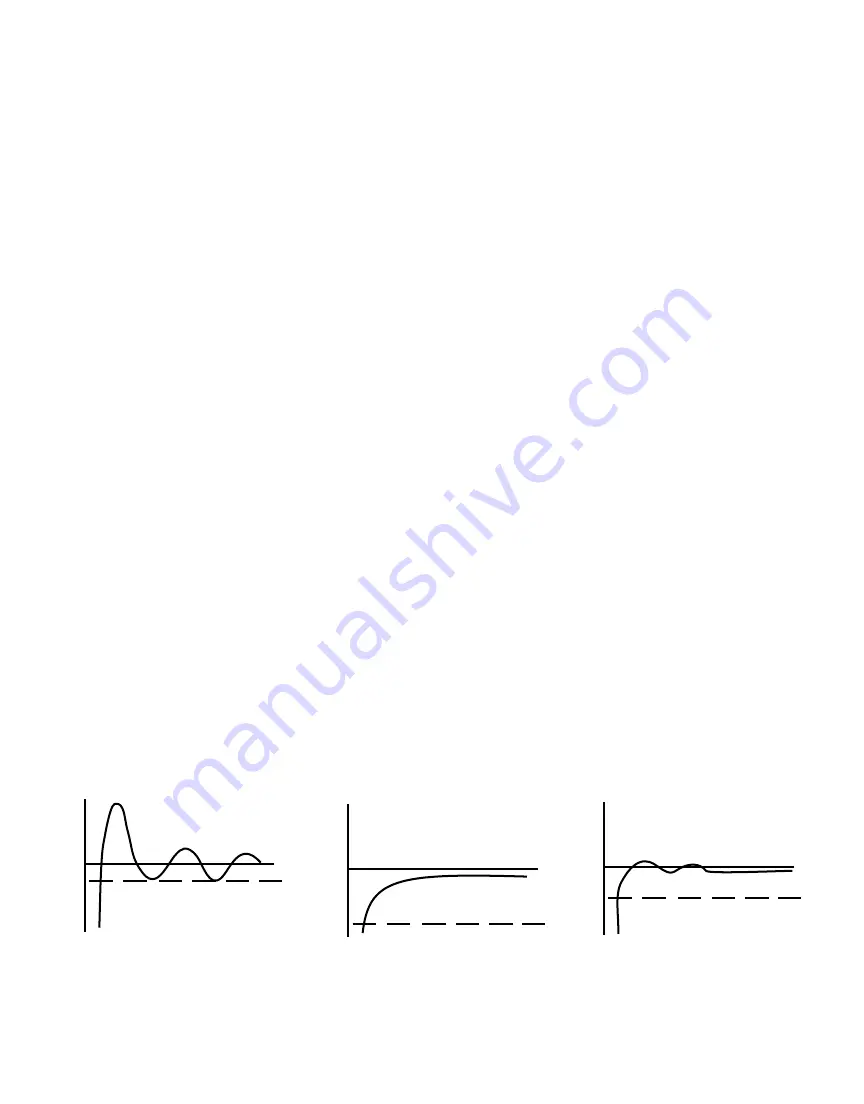

PV

Proportional Band

Too Small

Time

Proportional Band

with Correct Width

PV

Time

Proportional Band

Too Large

PV

Time