3

How Audio Gets Into a DAW

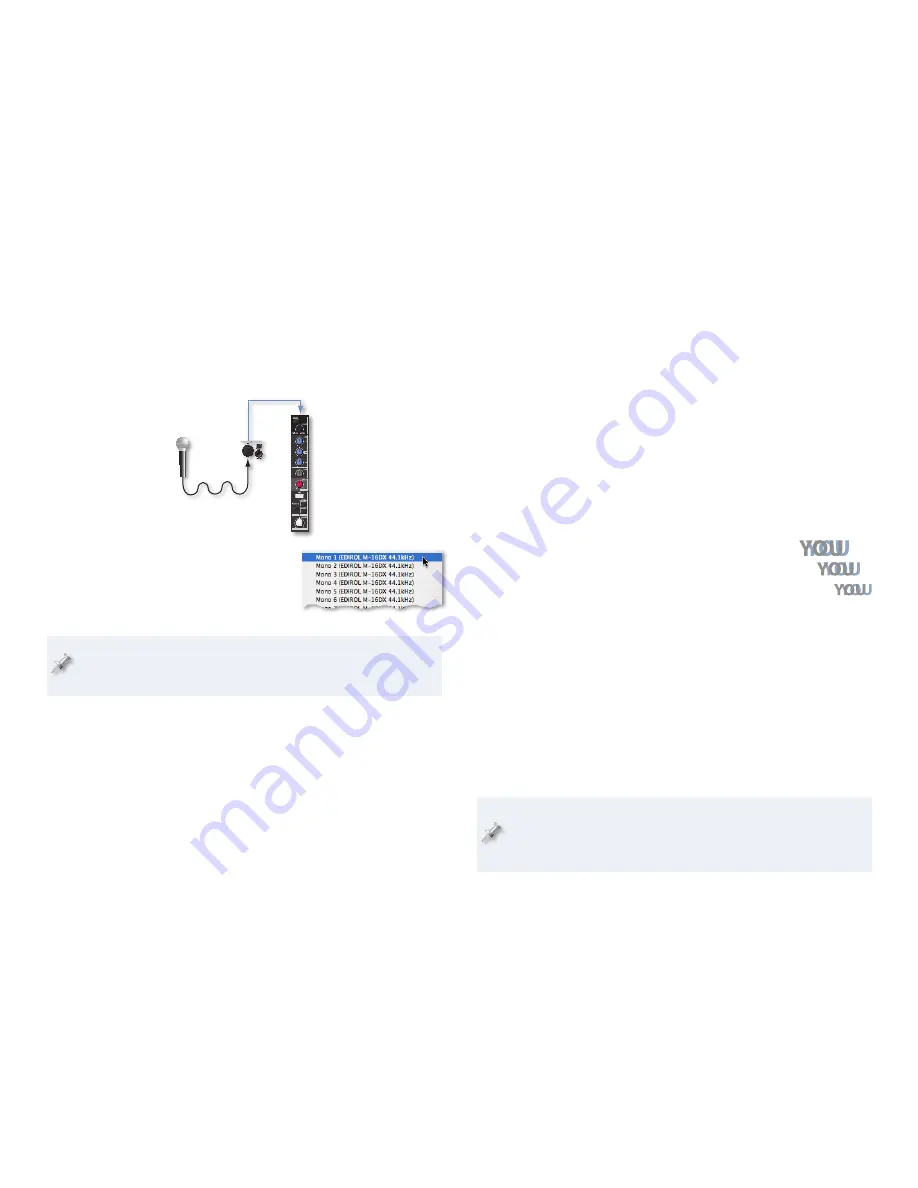

Once you’ve set everything up:

Audio arrives at an M-16DX input channel—

•

When you connect a mic,

instrument, or other audio device to an M-16DX input jack, its audio is

automatically routed to the corresponding M-16DX input channel.

You select the desired M-16DX channel

•

or main mix bus as the audio a DAW

track will record—

Each track in a DAW

can record audio from any M-16DX

input or its main mix bus.

Once you’ve recorded audio into a DAW, any changes you want to make

to the recorded audio’s sound get made in the DAW itself, including any

effects you want to add. When you mix, you also mix inside the DAW.

How You Listen to What You’re Doing

When you’re working with a DAW, your listening, or “monitoring,” setup

depends on the kind of session you’re working on:

In a multitrack session—

•

you record voices and instruments on their own

tracks. You can use this technique for building an arrangement a track-

at-a-time, or for doing a live recording of an entire group. Each track

records audio from a single M-16DX mono or stereo input channel.

In a two-track session—

•

you capture a final musical performance by one

or more musicians on a single stereo DAW track by recording from the

M-16DX’s main mix bus.

About Multitrack Session Monitoring

Latency

While modern electronic devices do things astoundingly fast, things still

take a

little

time to do. It only makes sense that it takes some time for audio

to travel from a voice or instrument to an audio interface, then through a

cable to a computer’s hardware, through that hardware to the computer’s

system software, from that software to a DAW’s track, and then from the

track to your ears. The musical ear is very sensitive to even tiny timing issues,

which—of course—amount to rhythmic issues in music.

The lag in time that occurs as audio travels from a mic or instrument into

and out of a DAW track is called “latency,” and it’s enough of a lag to make

performing perfectly in time along with the DAW’s metronome or already

recorded tracks difficult, or even impossible with a slower computer.

This is because when you listen to yourself through a

DAW while recording, latency causes the “you” that you

hear to be late compared to the DAW’s timing. What

you’ll hear is rhythmically a bit off—just how bad the

latency is depends on the speed of your computer

and a few other things. Even though your recorded

performance may actually be in time, that’s not what

you’ll hear as you record.

Fortunately, there’s a solution.

Zero-Latency Monitoring

When the M-16DX is connected to a computer via USB, the audio output

of the computer is returned to the M-16DX through its stereo USB channel,

Channel 13/14. This allows you to monitor the DAW’s output side-by-side

with what you’re currently recording using zero-latency monitoring.

With faster systems, latency can be more subtle, and you may choose

to listen through the DAW as you record anyway so you can hear the

DAW’s effects. Still, since there’s always some lag no matter how fast

your system is, we generally recommend zero-latency monitoring.

What you hear is not

what you get.