13

The mineralogy of the surrounding rock may also cause local

variations – even the complete reversal of the field in some

rare cases.

A representation of the Earth’s magnetic field is shown

in

Figure 1

. Note that Magnetic North is a few degrees away

from True North and that the Magnetic North Pole is actually

a ‘south pole’. The arrows on the magnetic field lines show

the direction which a compass needle placed on that line

would point. Opposites attract, and the north-seeking pole

of the compass needle is attracted to a south-seeking pole

in the planet’s core.

The strength and direction of the Earth’s field also varies

with time. The Earth’s molten iron core is in constant motion,

and the position of the North and South poles on the planet

is gradually changing. Map makers mark the deviation

(and the rate of change of this) on their maps.

The field also varies as a result of the interaction of the planetary

magnetic field with the solar wind and, at times, this can make

the field noisy and unpredictable. The M-Scan compensates for

all these changes to make finding objects in the ground easier.

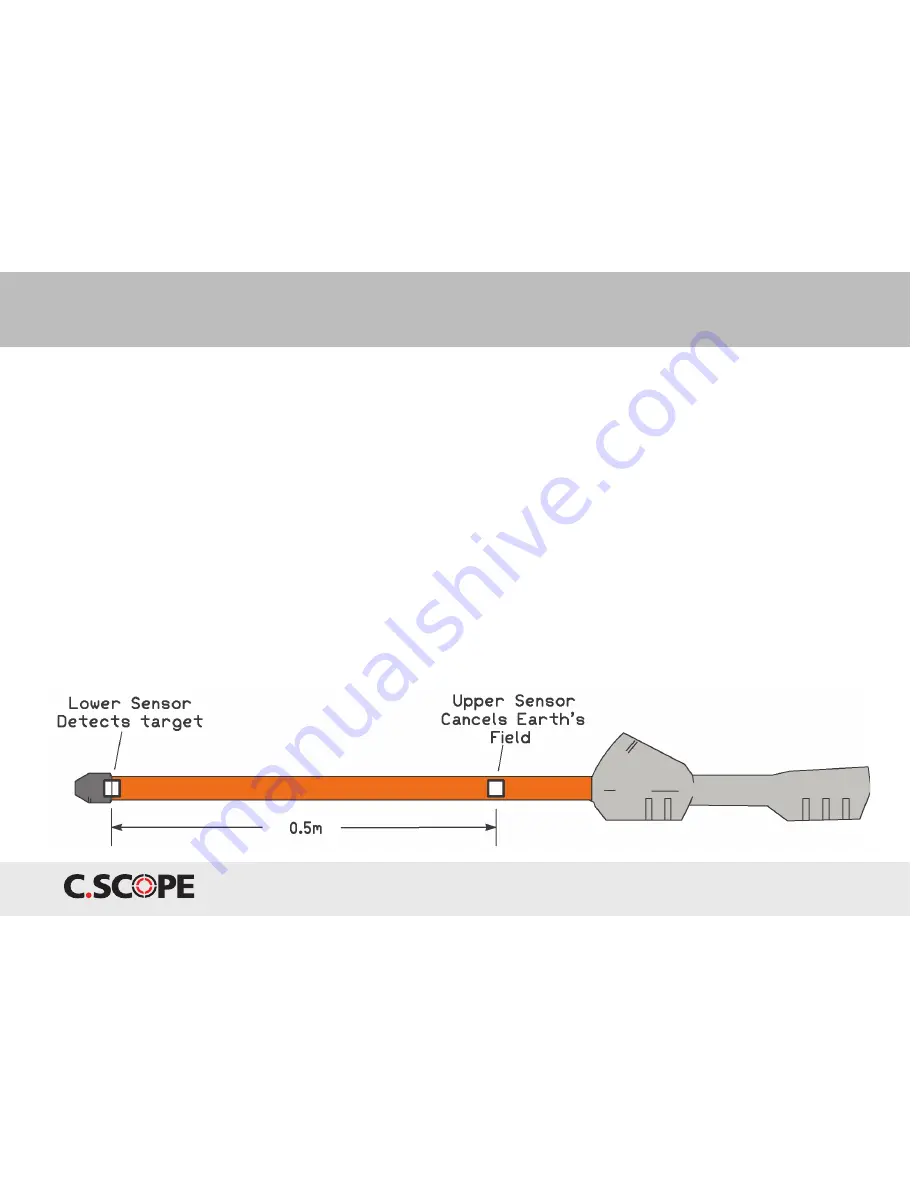

The M-Scan has two sensors in the long metal tube, spaced

approximately 20 inches/ 50cms apart. The upper sensor,

that is the one closest to the control housing, mainly picks

up the “background” field - usually the Earth’s magnetic field -

and the electronics uses this to cancel out the background

field. The lower sensor is closest to the ground, and is

more strongly affected by the field from target object

in the ground. This differential arrangement is sometimes

referred to as a “gradiometer”. It makes the M-Scan insensitive

to the Earth’s field, whatever its orientation and strength.

Figure 2 The C-Scope M-Scan with two sensors spaced apart.

Application Note 1. Understanding the M-Scan Magnetometer

Summary of Contents for M-SCAN

Page 1: ......